The Making Of Tekken with Yutaka Kounoe

Wonkey ON

Wonkey ON  Sunday, May 3, 2015 at 12:20AM

Sunday, May 3, 2015 at 12:20AM Awhile back, I managed to get my hands on a transcription of the 'Making of Tekken' Interview in the #104 issue of Retro Gamer Magazine with Yutaka Kounoe but for some reason or another I eventually ended up forgetting to share it with everyone. There's a lot of development background information that is especially interesting for anyone that is curious on the development of the early Tekken games so I feel like this is great to put out there. This interview goes in depth with a game developer who did work on the first 3 Tekken games while he was working in what he considered to be 'Namco's golden era.' Yutaka Kounoe currently no longer works at Namco and has since moved on to found his own indie game development company: O-Games. This interview was published around June, 2012 so it's been awhile from now.

▌The Making of TEKKEN [Retro Gamer #104]

̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄

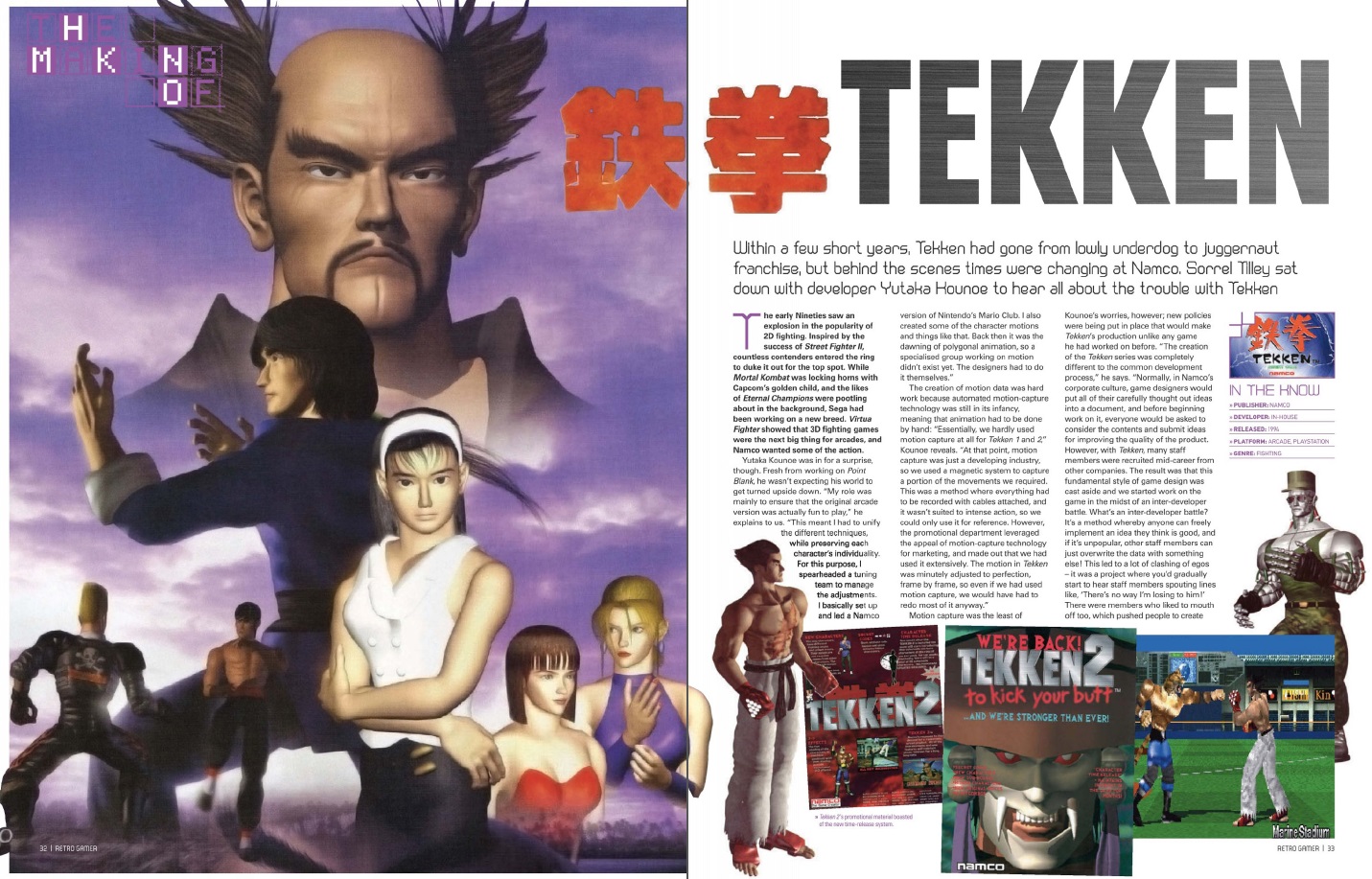

Within a few short years, Tekken had gone from lowly underdog to juggernaut franchise, but behind the scenes times were changing at Namco. Sorrel Tilley sat down with developer Yutaka Kounoe to hear all about the trouble with Tekken.

The early Nineties saw an explosion in the popularity of 2D fighting. Inspired by the success of Street Fighter II, countless contenders entered the ring to duke it out for the top spot. While Mortal Kombat was locking horns with Capcom's golden child, and the likes of Eternal Champions were pootling about in the background, Sega had been working on a new breed. Virtua Fighter showed that 3D fighting games were the next big thing for arcades, and Namco wanted some of the action.

Yutaka Kounoe was in for a surprise, though. Fresh from working on Point Blank he wasn't expecting his world to get turned upside down. "My role was mainly to ensure that the original arcade version was actually fun to play," he explains to us. "This meant I had to unify the different techniques, while preserving each character's individuality. For this purpose, I spearheaded a tuning team to manage the adjustments. I basically set up and led a Namco version of Nintendo's Mario Club. I also created some of the character motions and things like that. Back then it was the dawning of polygonal animation, so a specialised group working on motion didn't exist yet. The designers had to do it themselves."

The creation of motion data was hard work because automated motion-capture technology was still in its infancy, meaning that animation had to be done by hand: "Essentially, we hardly used motion capture at all for Tekken 1 and 2" Kounoe reveals. At that point, motion capture was just a developing industry, so we used a magnetic system to capture a portion of the movements we required. This was a method where everything had to be recorded with cables attached, and it wasn't suited to intense action, so we could only use it for reference. However, the promotional department leveraged the appeal of motion-capture technology for marketing, and made out that we had used it extensively. The motion in Tekken was minutely adjusted to perfection, frame by frame, so even if we had used motion capture, we would have had to redo most of it anyway."

Motion capture was the least of Kounoe's worries, however; new policies were being put in place that would make Tekken's production unlike any game he had worked on before. The creation of the Tekken series was completely different to the common development process," he says. "Normally, in Namco's corporate culture, game designers would put all of their carefully thought out ideas into a document, and before beginning work on it, everyone would be asked to consider the contents and submit ideas for improving the quality of the product.

However, with Tekken, many staff members were recruited mid-career from other companies. The result was that this fundamental style of game design was cast aside and we started work on the game in the midst of an inter-developer battle. What's an inter-developer battle? It's a method whereby anyone can freely implememt an idea they think is good, and if it's unpopular, other staff members can just overwrite the data with something else! This led to a lot of clashing of egos - it was a project where you'd gradually start to hear staff members spouting lines like, 'There's no way I'm losing to him!' There were members who liked to mouth off too, which pushed people to create things of such high quality that nobody would be able to say a word against them. That's the kind of unprecedented project it was."

The wiki-style development process led to motion data being overwritten without warning, combo techniques being joined up and disconnected, and daily modifications to characters' costumes. This constant stream of additions and alterations formed a bottleneck, and Kounoe's tuning team was working in it. "I set up the tuning team for the original Tekken, and steadily expanded it by adding new staff members," he remembers. "It went from just one part-timer and myself to 30 employees at its height. In my student days, I would spend each month aiming for the highest arcade scores in Japan; in my tuning team we had all taken up the job of high scorer. Those who 'graduated' from the team were later chosen for top producing and directing positions, and now they hold up the Namco brand. The members were all workaholics; we lived at the office. We used to line up chairs to sleep on because the floor was cold. We were constantly suffering from sleep deprivation because we had to test that every technique for every character functioned normally, so one by one we tried the moves in every direction to confirm they worked. If the tuning team didn't exist, there would have been no Tekken. It was built by the earnest hard work of the staff.

"There was a mountain of problems with the project, most of which were resolved by the wrath of the major staff members. There was a very fierce and passionate collision of game design philosophies. There was also a very low level of efficiency, and the amount of work that each person produced was huge. Consequently, there was an unprecedented variety of ideas, rather than it being the creation of one designer. We ended up with a very bizarre game. The result of this was that unregulated raw materials were being implemented one after another, so the work of the tuning team became extremely difficult - having to retain the characteristics of each of these elements while balancing performance. With a normal development schedule, you make a plan that separates the raw elements so the differing styles and abilities are easily distinguished, and the man-hours required of the tuning team are small. With Tekken, designers were becoming obsessed with their own ideas, and continued implementing them at random. Trying to differentiate these ideas after they'd been added was a process you could hardly call normal. I felt like I was solving a giant puzzle at the same time as making a game."

Kounoe and his colleagues were no strangers to all-nighters, but this was the first time inefficiency and competitiveness had been the cause. What caused this change? "There are many reasons for the change at Namco. As a fighter, Tekken's game flow was simple, but there was a lot of data for all the techniques, so compared to a regular project, the management style was different off the bat. The original Tekken was also the very first 3D fighting game to be made at Namco. There was the increase in employees halfway into production, which meant the culture of other companies got mixed in. I think our development speed seemed very slow to the new team members, and our trains of thought were more restrained. We weren't very assertive either, so the new guys couldn't tell what we were thinking. Of the newcomers, some were brought in specifically to work on Tekken, some for other reasons. Namco's culture was unique, and I could see these newcomers struggling. Some of them liked to row with everybody, but those people didn't stay at the company long. The Tekken project was like a storm; for varying reasons, many talented developers quit the company."

Understandably, there was a growing pile of discarded ideas - victims of the inter-developer battles and the ensuing delays. "In the original, the development ran over schedule, so we couldn't include sideways rolls when characters got up from the ground," Kounoe recalls. "For Tekken 2 Yoshimitsu's designer came up with a penguin fighter. At that time we were trying to think of animals that walked on two feet that we could base on the pre-existing human animation patterns. At any rate, the designer quit the company before he could complete the character model and I don't think many people in the team even knew about the penguin idea. These kinds of problems carried over into Tekken 3 - I wanted to incorporate more strategic play into air combos by introducing safe-falling techniques, but I couldn't complete it because other staff members failed to understand it. That wasn't all. Stances, damage animations, pinning techniques - all these elements got canned because people vetoed them based on their personal preferences.

"Now that I think of it, I remember there were also plans for a playable salmon in Tekken 3, but it was rejected. Kuma was going to wield a frozen fish, like Yoshimitsu's sword. After a timed release, you would have been able to control the salmon on its own, just flopping about on the ground. The plan was for a weak character with a jump and tail-spin attack. I don't remember exactly why it was cancelled. Probably some know-nothing dev obstructed its progress. What a pity. If we'd added the salmon, it would have made people burst out laughing and it would have become a talking point among high-level players because it would be so difficult to win with."

The freedom to act alone was something of a double-edged sword, also working in the game's favour on occasion: "Almost everything that was added was also decided by individuals working alone. Nina's throw combo was added by someone working on motion. I handled the motion for Devil, and a programmer later added his wings and laser beam. The ten-hit combo was overpowered and could lead to players shaving their opponent's health down to nothing in an instant, so my tuning team stepped in and made some minute adjustments and saved it from being scrapped."

"Tekken was designed with the aim of creating a game that was different to Virtue Fighter. We focused on unrealistic characters like Devil Kazuya and Kuma. So long as it was flashy and seemed possible, we would try anything. The whole team put in their best efforts to make a fun game, even with the low-performance hardware we had. The problem was that Tekken 1 and 2 had large portions created by staff from outside Namco, so we couldn't control the project. This is why it turned into such a weird and flashy game. I think its strangeness makes it fun, though. In other words, the first two games were created as an experiment; even the developers couldn't predict how it would turn out. That's the appeal of Tekken. The third game, which I was in charge of, was a more calculated production. It was systematically planned and controlled, which meant it was more subdued, but I think it turned out well."

So does Kounoe like the recent effort between Capcom and Namco? "I have no interest in the Street Fighter X Tekken crossover. I haven't played it. The Tekken that emerged after I left has fallen below my expectations. It's a lot easier to create 'arrangements' of old games than to make something new. To still be relying on Tekken even now is proof that Namco's real strength has disappeared, and I'm shocked by the decline in creativity and development ability. It's shameful to call yourself a developer or a creator if you can't design new games. Relying only on collaborations that will sell well shows a lack of imagination, and it's not going to set the world on fire."

▌TICK, TOCK, TEKKEN TIME BOMB

̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄  ̄

THE ADDITION OF eight new characters brought Tekken 2's crew of brawlers up to a meaty 25. Such a bustling roster could have been overwhelming to Tekken newbies, so Kounoe devised a clever bit of technical trickery to resolve the issue and keep punters coming back for more: "I drew up and implemented a plan to prolong the game's life. In the Tekken series we have enemy characters called sub-bosses who match up with the character you have selected. but it would look too complicated if you could choose from so many fighters right from the off, so I employed a system that would release them steadily - that way, players could learn the game gradually. The problem was that if the characters made calendar-based debuts it would have infringed on another company's patent! That's why I had to design our own proprietary system, which measured how many hours the cab had been on for."

This also ensured continued interest in Namco's machine at a time when new fighting games were popping up all over the place. To complement the time-release system, a number of characters could also be unlocked by entering codes that the players were left to figure out for themselves.

--

Special thanks to the Blonde Bomb Mag site for unintentionally reminding me I had this!